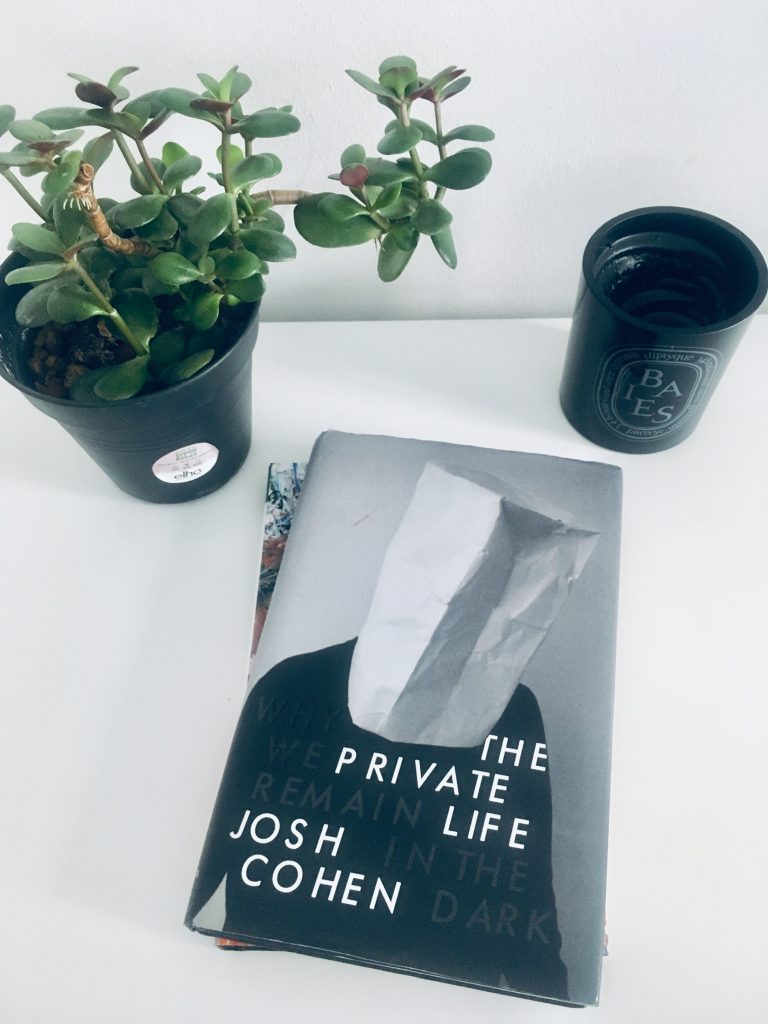

The Private Life: Why We Remain in the Dark by Josh Cohen

It is a probing question for humanity and one that has racked the brains of writers, analysts and philosophers. How much can we know of others and how much can we know of ourselves?

In “The Private Life: Why We Remain in the Dark” – psychoanalyst and professor of modern literary theory at Goldsmiths in London takes us on a quest, despite living in a culture that floods our lives with light, to explore the private hidden life that we all contain. Using his experience as an analyst, a literature professor and a human he takes us on a journey exploring the dark terrain of our innermost selves.

He writes of our aversion even to the idea that we may not even know our own selves, that parts of ourselves remain hidden even from ourselves:

“The possibility that there may be something that you not only don’t know (which can always be remedied) but can’t know, and which nonetheless is at the heart of who and what you are, is peculiarly affronting.”

“The first premise of psychoanalysis is that the very existence of a private zone of inner life – what psychoanalysis calls the unconscious- is so unbearable that we spend most of our lives and energies denying it”

There is a war raging over the private sphere in our modern age, what Cohen describes as a “pathological intrusiveness”. We are living in the golden age of social media culture, all encouraged to share and encounter the private lives of others and ourselves all the time.

But what if this anxious drive to make everything known is futile; what if what we call private life is the one element in us that we can’t possess? Could it be as Cohen suggests: “The right we assert to know everything about everyone else may be nothing less than an unconscious protest against the ignorance of ourselves.”

The famous British psychoanalyst DW Winnicott spoke directly to our essential paradox: “ I think one can detect an inherent dilemma, which belongs to the co-existence of two trends, the urgent need to communicate and the still more urgent need not to be found”

This is always the paradox in the comfortable cocoon of the consulting room. Cohen describes his own experience of psychotherapy and his compliance and excitement at exploring his internal world with an interested participant. One day he somehow gets lost on the way to his session and arrives 15 minutes late. The experience jars him as he arrives in a cloud of confusion and distress. He writes of the experience of not knowing what happened.

“A simple observation came to condense a range of different meanings. First, apparently I did not want to come here as much as I thought I did. My commitment to psychotherapy screens out my hostility to it….and yet I want to protest:I don’t want to come here? Me, with my fearless curiosity about myself, about analysis? What would possible make you say I’d want to be somewhere else?

Second, analysis will take me where I didn’t think I was going. Wherever I imagined my explanations and avowals and speculations were leading, it wasn’t here, confronted with my wish to be miles away, to tell analysis and therapist to fuck off, to be spared the ache of self-knowledge. Whatever I find out in analysis will be despite, rather than because of, my conscious efforts. I’m not the intrepid mariner of my inner life, effortlessly navigating its boundless waters, but its hapless passenger, borne and blown by its ferociously unpredictable waves. I don’t know where I’m going, least of all when I think I do.”

Cohen then explores this concept of ‘private life’ as the presence in us of someone else, an uncanny stranger both unrecognizable and eerily familiar, who can be neither owned nor controlled.

“The desire to express your pure, naked self to bring it into the light of day, can only end in frustration, in the feeling that what you wanted to show remains in the dark. Whoever’s reading or listening is liable to make of your words something quite other than what you thought you meant.

And this is what as Cohen points out can shake us out of a complacent and comfortable place of thinking we know ourselves. There is no one self, “to say everything isn’t to arrive at the definite truth of your inner self, but to expose it as double, both you and someone else, unimaginably courageous and unspeakably cowardly, honest and dishonest to a fault.”

Our private lives are perhaps not entirely knowable but they are mines of personal meaning and personal experience, meaningful precisely because they are private. There is a freedom in the private framework of the mind and the body, which belongs to each and every one of us, and in a completely unique way. The second that this private realm is torn from where it belongs, it becomes mere performance or drama. This is the moment that the rich complexity of its meaning, self-expression and creativity is diminished.

Cohen ends on this note, “And yet I cling to this desire, in the knowledge that private life, mine and everyone else’s, is finally incommunicable, that the passage between my inner life and yours is hopelessly treacherous, that most of what I’ve tried to claw from the interior has been lost or distorted somewhere in the tunnel that separates us. You could say rightly, that this persistence in remaining in the dark is cause for despair. But also, and equally rightly, that it’s our only hope.”